Respond to these rapid questions in our The Quiet Girl quiz and we will tell you which The Quiet Girl character you are. Play it now.

The nameless narrator of Claire Keegan’s award-winning 2015 short story Foster is a young girl living in rural Ireland who has been sent to stay with relatives she has never encountered while her mother has another child. There are already too many mouths to support. One might anticipate the story to end in horror, with the child being thrown to the wolves. However, this is not the case. The childless couple treats her with the first kindness and concern she has ever known. “I keep waiting for something to happen, for the ease I feel to end,” she says, “but each day goes on much like the one before.” Keegan’s writing is founded on observations made by a youngster. The infant piece together the world from fragments, overheard or glanced events. Foster is an expert at eliciting a child’s point of view.

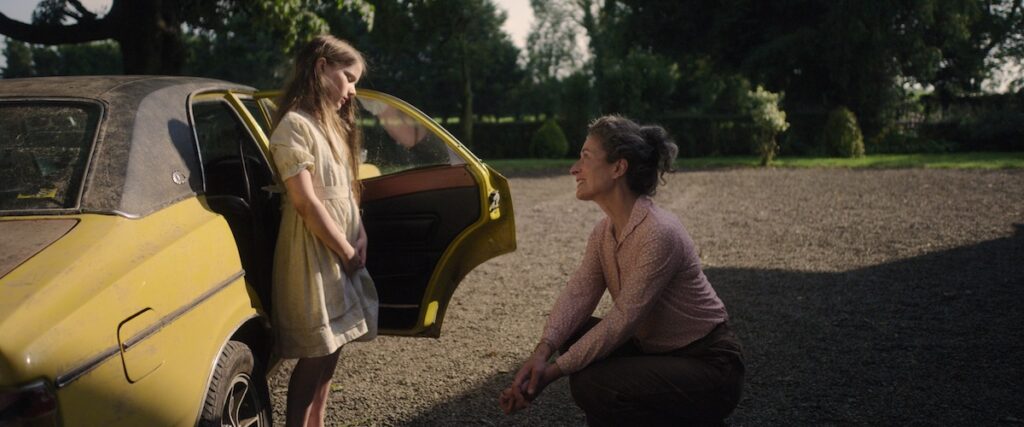

“The Quiet Girl,” adapted for the screen and directed by Colm Bairéad, admirably retains this point of view, keeping the frame of reference narrowed to the world as seen through the girl’s eyes for the most part. Bairéad has made some changes to the source material, opening up the narrative a little bit with a sort of prologue—her life at home, her bed-wetting, her proclivity to disappear for hours at a time. The primary difference, however, is the most visible. “The Quiet Girl” is an Irish language film, with 95% of the dialogue in Irish and only a few English phrases thrown in for good measure. (there are subtitles for both). “An Cailn Ciin” (The Quiet Girl) is the first Irish-language film to be nominated for an Academy Award (this year’s Best International Feature). It’s a watershed moment in Irish cinema.

Cáit (Catherine Clinch), the girl’s new moniker, is a wary and watchful figure. She has endured her chaotic neglectful home life—her drunken father, her harried mother—by shrinking and stilling herself. Kate McCullough’s sensitive photography immerses us in Cáit’s sometimes dissociated but always vigilant viewpoint. The attention is drawn to the details: the dizzying blur of trees outside the vehicle, the high-flung blue sky peeking through, the inky-black darkness of a bar’s interior at noon, the way shafts of sunlight pierce through still pools of water. Adults are viewed from the side or from below. Cáit regards them as unfathomable riddles.

The production design—objects, cars, televisions—makes it obvious that “The Quiet Girl” does not take place in modern-day Ireland, but the year (1981) established in the novella with a mention of hunger strikes in the North isn’t nailed down. (unless I missed it). “The Troubles” are nowhere to be found, nor is the outside world. This is the timeless rural landscape, where hay must be brought in, cows must be milked, meals must be made, and Mass must be held every Sunday. Cáit lives in squalor and neglect at home, with a father who is too preoccupied drinking to ensure the hay is delivered on time. The home is crawling with children, all of whom are girls. Cáit’s destiny is predetermined without her knowledge. One day, she is taken down to Wexford and dropped off at her mother’s cousin’s house.

But you shouldn’t waste any more time and start this The Quiet Girl quiz.

Eibhln (Carrie Crowley) and Seán (Andrew Bennett) are both in their forties and own a farm. Their property, on the other hand, is well-run and orderly. Cáit stands in the spotless, well-lit kitchen, staring around her. She can’t believe such purity and tranquillity exist. It’s a different universe. Eibhln assumes command the moment he sees Cáit’s filthy dress, dirty hands, and filthy legs. She bathes the child, takes her to her room, and requests if the curtains should be drawn at night. Her demeanor is both soft and pained. Cáit has never known a thoughtful adult who has asked her what she desires. Seán is quiet and distant, making him difficult to interpret at first. Is he irritated by the appearance of the child? He scarcely looked at her.

Cáit’s new existence has begun. Eibhln instructs her on how to prepare, clean, and draw water from the well. Cáit finds solace in the routine of daily chores and the care given in the running of daily life. The story develops like a dream. Light and shadow, bird noises, fresh veggies, the well’s mirror-like water… McCullough and Bairéad carefully explore the environment, allowing it to evoke and putting us in Cáit’s shoes.

The Quiet Girl Quiz

On the outside, not much occurs. She’s being driven to a burial. A gossipy lady questions Cáit about Eibhln. However, existence isn’t made up of dramatic events. The individuals in this story are not particularly expressive. When Seán or Eibhln do communicate themselves, they do so authentically. Every remark matters. The emotions beneath are immense.

Also, you will find out which character are you in this The Quiet Girl quiz.

There is a backstory for Eibhln and Seán—an event about which neither can talk (but which is readily guessed), but the film isn’t about the big reveal. It’s the little things that count. A cookie put on a table brings an explosion of emotion and meaning. A biscuit is more than that. A serious conversation by the sea on a moonlit night can be profound and possibly life-changing. It is said that even one “witness” to a neglected child’s suffering can make or break that child’s future. “The Quiet Girl” provides Cáit with two eyewitnesses. The significance of this is not stated explicitly, and Cáit will only understand it in retrospect, but a difference has been made. Bairéad’s patient care in allowing the characters to disclose themselves is the reason we “get” it. Nothing is hurried.

Some of the presentation is repetitive, such as the repeated shots of the kitchen, the walk to the well, the daily chores, and Cáit’s wariness gradually melting into confidence. The repetition exists for a reason and serves a function, but a little goes a long way.

About the quiz

The final sequence, which completely knocked me flat, makes it clearly obvious how little and how long it goes. It was only then that I realized how well “The Quiet Girl” worked. The picture operates undercover.

Also, you must try to play this The Quiet Girl quiz.

The Irish language is required in Irish schools, but its past is one of suppression. Road signs in Ireland are bilingual, and there is an effort to preserve the practice, promoting cultural continuity. The first Irish language sync sound film, “Oidhche Sheanchais” (1935), started the history of Irish language films in the early decades of cinema. (Long thought lost, it was recently discovered, and a fragment can be seen on YouTube.) Flaherty is best known for directing the “documentary”—quotation marks required—”Man of Aran” (1934), which is still criticized today for Flaherty’s fictionalized version of Irish life, especially the characters all speaking in English. Other notable Irish-language films include George Morrison’s “Mise Éire” (1959), a true documentary about the 1916 Easter Rising, Bob Quinn’s crime drama “Poitn” (1978), the first Irish-language narrative feature, and, more recently, Robert Quinn’s “Cré na Cille” and “Foscadh,” directed by Seán Breathnach. Other Irish films have used both the Irish and English languages, making them effectively bilingual.

“The Quiet Girl” goes all the way and is groundbreaking in terms of both language and success within a recent movement of accomplished Irish film. The cultural significance of “An Cailn Ciin” is encapsulated in the tiny insert shot of a cream-filled cookie put on a table. Everything changes at that point. Nothing ever will be the same again.

The film will be released in cinemas on February 24th.